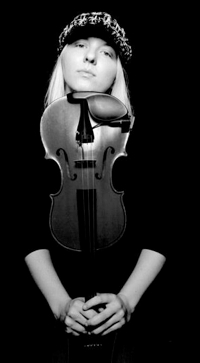

BETHANY HANKINS

Suzuki

&

The Childhood of Culture

By Patti Druliner

Edited by Bethany Hankins

Shinichi Suzuki has had a profound impact on the teaching of music. Since language is one of the most complex skills human beings acquire, Suzuki concluded that we are vastly underestimating the potential of children. What is different about the way we teach language and the way we teach everything else? This is what Suzuki set out to discover, so that children everywhere would be able to utilize their exceptional potential for excellence in music. The following elements form the core of the Mother Tongue Approach to music education.

Expectation

Parents of infants do not anxiously bring their child to an expert and ask if the child is gifted in speech. All parents not only assume that their child will learn to speak, but also expect that their child will be quite successful at speaking. In the same way, Suzuki expects all children to be highly successful at music, even to the point of looking gifted by current standards. The children who learn from teachers well-trained in the Suzuki method bear out this expectation.

Prenatal and Infant Learning

Research has shown that children hear and develop preferences for certain sounds while in the womb. Children are beginning the process of learning their mother tongue from the womb onward. Language learning is not delayed until school age; neither does Suzuki delay the learning of music until school age. And because he uses the techniques of infant language instruction, this learning of music is as natural for the child as the learning of language.

Sound in the Environment

All children learn precisely the language they hear, Japanese children from Osaka learning that dialect and U.S. children from Georgia learning that accent. One does not have to guess what language an infant will learn; one only has to listen to what is being spoken in his environment. Suzuki capitalizes on this natural ability, teaching parents how to structure an environment in the home that exposes children to the sounds of music. Recordings of the music the child will learn are played very quietly throughout the day: during play time, in the car, getting ready for bed, etc. These recordings are the equivalent of the on-going language of adults that the infant hears daily in his home.

Small Steps

We see parents of infants being delighted with any syllable their child says. Each vocalization, no matter how small, is a happy occurrence. Parents do not expect the Gettysburg address; rather they look for and are happy with small steps of progress.

Speech First, then Reading

If reading and speaking were required to be taught simultaneously, language development would certainly be delayed in children and probably severely limited in many. In the same way that we expect children to speak before learning to read, Suzuki has children become basically proficient in playing music before beginning to read scores.

Encouragement

Parents do not criticize the language mistakes of infants; they repeat the correct sound and let the child know how happy they are when the child makes some approximation of that sound. This loving atmosphere produces the singularly advanced achievement of speech. In the daily “home lesson,” Suzuki parents supply loving attention to the music-making of their child, offering delicate guidance and delighted response to each little progress.

Repetition

In teaching speech, parents again and again say the sound they want the child to imitate. As a child learns a word, he can be heard repeating it. As he learns new words, he does not abandon the ones already learned, but rather plays with them in combination with the new words. Suzuki noted that this very practice – this playing with language – is what creates skillful speech. Applying this idea of repetition to music is one of Suzuki’s greatest contributions. He realized that once selections of music are learned, we are then free to “play” with them. We are free of learning the piece (how to say the word) and we can begin to uncover for ourselves the grammar of feeling and the syntax of tone. This is the reason Suzuki students spend much of their music time, on their own and in groups, playing around with pieces they already know, thereby learning skillful musicianship and developing the ability to create and refine a beautiful sound.

Parent as Teacher

Language is not taught by specialized teachers in community facilities, but through the conversation the child hears in his home. Parents are the teachers of language; just so, they are the co-teachers of music in the Mother Tongue Approach. The parents insure that the recordings of music are played as often as possible, emulating the audible language the child hears in the home. The parent teaches the daily “home lesson” in which she supervises the new learning assigned that week by the studio teacher, and then fosters the development of skill and musicality by review of previously learned repertory – all of this done in the same attentive, patient way in which she teaches her child language. The parent, teacher, and student form a team, the Suzuki Triangle.